I read three books translated by Jamie Bulloch in quick succession, The Mussel Feast, Love Virtually & Every Seventh Wave and so I asked him if he would mind answering some questions about the translation process and his experiences as a translator. Here’s what he had to say.

Please give me a short biog of yourself.

Studied Modern Languages at undergraduate level, then Austrian history for MA and PhD. Worked briefly as schoolteacher, teaching French and German; later lectured at a number of different colleges, teaching German language, German History and Central European History. Translator of literary fiction since 2007. Twelve translations published to date (inc. two non-fiction) and two more in production. Author of Karl Renner: Austria – history book, part of Haus’s series Makers of the Modern World. Live in London with wife and three daughters.

How did you first get into translating fiction?

During my PhD and for a couple of years afterwards I worked as a history lecturer, principally in London. My aim was to continue with an academic career, but prospects of a permanent job were very poor (I had till then been filling in for other people’s sabbaticals, teaching a wide range of history courses). I had already been doing a small amount of translation work, but this had been limited to agricultural econimics (a subject in which I am no expert, but have learned a lot about over many years of translating it!) My break into translating literary fiction came when Christopher MacLehose – for whom my wife had worked at The Harvill Press and was now undertaking editorial commissions – asked whether I should like to produce a sample of a psychological crime novel he had bought. He liked what I wrote and so the job was mine. Other jobs came on the back of this first novel and now I am fortunate – for the moment, at least – to have as much work as I can realistically cope with.

Could you tell me about the translation process? Where do you start?

I do not have hard and fast rules or any particular theory about translation, as each book presents its own challenges. Usually, and ideally, I will read the book first and then I will dive straight in. My overall strategy is to translate fast, maintaining a good momentum, and then edit my work slowly and thoroughly, putting the German original to one side. At the forefront of my mind is the imperative that the book should read like a good piece of English, so I polish and polish until I’m happy. The copyeditor takes care of the rest.

Where do you do most of your work?

I do have my own study at home, but at present I’m working in the kitchen because we have underfloor heating and it’s freezing upstairs.

When you first read a German manuscript, do you immediately hear the translation or is it not as straightforward as that?

Whenever I read a German novel, either in preparation for translation or to write a report on for a publisher, I can’t help stopping occasionally and wondering how I would translate that particular phrase. But first appearances can be very deceptive. What masquerades as a page-turner in German can turn out to be very tricky to translate, and vice-versa. Love Virtually and Every Seventh Wave are good examples here. Both come across as very simple when you read them in the original, but finding the right voices, conveying all the wordplay without sounding irritating in English took quite a long time. By contrast, Friedrich Christian Delius’s Portrait of the Mother as a Young Woman, which is a novella in a single sentence, looked at first glance like a nightmare, but ended up being a fairly straightforward job. Naturally, I was delighted when reviews praised my translation of that book, but I have to admit that the Glattauer novels presented the greater challenge.

What is your most important tool that you couldn’t work or translate without?

This is an easy one: the internet. How translators ever worked without it, I don’t know. They must have been squashed between hundreds of dictionaries and other reference books.

Do you ever suffer from “translator’s block?” If so, how do you overcome it?

Yes, but I don’t think it’s ever as bad as writer’s block. Often you come across a phrase which is incredibly difficult to translate. The best way around this is just to highlight it, move on, and return to the problem later.

You’ve translated several works by the same author (Glattauer and Hochgatterer), how much contact do you have with the author, if any?

It depends. Contact with the author can be vital as it is the only key to solving some apparently insurmountable problems. To be able to translate something you have to understand it in all its facets and in the most basic detail. Sometimes, therefore, I will ask an author what seems to be a really simple question. In the case of Paulus Hochgatterer, I asked him to make explicit some elements which were only hinted at in his novel The Mattress House. Only then could I reproduce the same nuance in English.

You translated Love Virtually/Every Seventh Wave with your wife Katharina Bielenberg. How did that work? did you sit together or translate the two characters in isolation?

We translated Leo and Emmi separately, then edited both books together, which was a long process, but two heads work much better than one.

Was this your first translating collaboration? How did you find it? How long did it take compared to a translation you might work on by yourself?

Yes it was and we both enjoyed it. We were able to be as honest and critical as we liked of each other’s work. In that way I think we ended up with a far better text. Yes, it ended up being a longer process, but only because our work included this joint copyedit.

What attracted you to the Love Virtually/Every Seventh Wave project?

The prospect of combining forces to translate the books was very attractive, and we had both enjoyed reading them a couple of years earlier.

Love Virtually & Every Seventh Wave are made up entirely of email correspondence, did this present any issues with the translation in terms of the sort of language we tend to use in emails?

Overall these books have been incredibly well received, both in the German-speaking world and elsewhere in translation. One of the few criticisms that has been levelled, however, is that the email language used by Emmi and Leo is not particularly realistic, i.e. many of their messages are quite long and grammatically correct, whereas people generally cut corners and are often very sloppy when using this medium. To a certain extent that is true, but let’s not forget that this is fiction and that the books have more in common with old-fashioned epistolary novels of the eighteenth and nineteenth century. Glattauer’s books may be very popular and commercial, but his prose is of high quality and anything other than sloppy. So, to return to your question, while some common features of email are certainly present in both books, where the prose read like a well-crafted letter we reflected this in the English translation.

Were there any parts of these books where you had to use some artistic license to get across the meaning, rather than use the literal translation?

I mentioned above that my chief aim when translating is to produce a good piece of English which does not read just like a translation. To achieve this you have to abandon the literal approach repeatedly. At the launch event for Mussel Feast, the author, Birgit Vanderbeke suggested that a translation had to ‘violate’ the original text to be successful. As a translator I would say that this is very encouraging to hear from the mouth of a writer, for in many respects you can only remain faithful to the original work by attempting something different. Jokes and rhyming verse are only two obvious examples of where the translator has to be very creative to be convincing. To follow on from what Birgit said, I would argue that two of the key attributes of a successful translator are self-confidence and courage. When faced with a tricky translation problem you cannot sit on the fence; you have to opt for one side or the other – so do it as if you really mean it.

Do you ever worry about the loss of meaning in translation, especially when something is very specific to the original language and culture?)

Again this all boils down to the confidence of the translator. You have to believe that the English version will be as good as the original rather than a pale imitation. Sure, there will be cultural elements that may get lost for a large proportion of readers, but what you must bear in mind is that in some instances they may well go straight over the head of a proportion of German readers too. I firmly believe that there is a solution to every translation problem; often the key to finding it is to think laterally. Or if something gets lost on one page, the translator can try to recover it in a different form on the next one. Another important point is that reading foreign literature in translation opens a window on the world, allowing an insight into a wealth of different cultures. I read a great many translations and find myself frequently looking up things on the internet that are new to me. All in all, we gain far more than we lose through translation.

As the translator, do you have any say in the translation of the title of the book? I personally think “Gut gegend Nordwind” is a much nicer title than “Love Virtually”!

That’s funny, because I came up with Love Virtually, having drawn up a list of about ten possible titles. We will often go for a direct translation of the original and I won’t have a say. In the case of Gut gegen Nordwind, the English equivalent ‘Good against the North Wind’ just smacks too much of a literal translation and was unlikely to attract too many readers. Aware of the commercial potential of the book, we decided we needed something far catchier. Just to be sure, we ran it past both the author and the original publisher, both of whom were happy with our solution.

I’ve also recently read your translation of The Mussel Feat by Birgit Vanderbeke, which is so very different from Love Virtually and Every Seventh Wave. What attracted you to this piece of writing?

It’s just an incredible piece of writing. The author told us that she wrote it start to finish in three weeks! I also enjoyed the challenge of capturing the style, especially the repetition of words and phrases throughout the novella.

The Mussel Feast is a breathless monologue, did it feel exhausting to translate?

Sometimes! I like to break at the end of a section or paragraph. There weren’t any in this book. And some of the sentences were so long that you feared you’d never get to the end. What was crucial when translating Mussel Feast was never to lose the thread.

What challenges did you face with this translation and how did it differ from Love Virtually/Every Seventh Wave?

The words and phrases which are repeated over and over again like leitmotifs were incredibly difficult to translate, because my solution might work eight times where a word/phrase occurred, and yet on the ninth occasion it was simply wrong, or stuck out. So I’d have to go back and find something which worked throught the novella. We also had to change the punctuation in English – chiefly by introducing more full stops and semi colons – to avoid too much confusion. In fact, the Glattauer books also contain oft-repeated words and phrases, so there were more similarities than at first might be apparent.

What’s the most difficult passage you’ve ever had to to translate to get the sense of meaning right?

Anything written by my stepfather-in-law, Karl Heinz Bohrer, who is a German professor of literature and aesthetics. He writes unbelieveably intricate paragraphs, full of conceptual compound nouns that could make a translator cry. We have a good laugh about it.

Do you ever re-read your translations and see sentences you would prefer to change?

I don’t really have time to re-read my own work, as there’s always another to be getting on with. But I suppose my own confidence increases with every book, and were I to translate some of the early books again I might do things a little differently.

For your own reading pleasure do you read in English or German? What is your favourite book?

I think it is imperative that a translator reads extensively in their own language, to improve their vocabulary, style and to get new ideas. For pleasure I read almost exclusively in English. But I also enjoy most of the novels I read in German for work. I’m very bad at citing favourite things, or top tens, but I have a very soft spot for Jonathan Coe’s What a Carve Up!, perhaps the funniest and most engaging novel I have ever read, and a dark satire of the greedy 1980s.

What are you working on now?

Timur Vermes’s Er ist wieder da, to be published by MacLehose Press next year as Look Who’s Back. This debut novel, which takes a satirical look at contemporary Germany through the eyes of a resurrected Adolf Hitler, has been a sensation in Germany since its publication in autumn last year, selling over 500,000 copies in hardback. It’s a very funny novel which also presents a serious critique of our superficial society, where style and medium is more important than the message.

Is there a German book you would love to translate – why would English readers like it?

One novel which I fear has slipped through the net is Kristof Magnusson’s Das war ich nicht (It wasn’t me), a brilliantly funny book set around the financial crash, whose three protagonists are an internationally acclaimed writer, a young banker and a literary translator (!). English readers would like it because it is plot-driven, very amusing and a complete page-turner.

Suggest a book that may surprise me – why should I read it?

If you are talking about books I have translated I would encourage you to try Katharina Hagena’s The Taste of Apple Seeds, which was recently published by Atlantic. I first read this book for another publisher, and was so charmed by the story that when I heard Atlantic had bought the rights I wrote to them immediately and begged to be allowed to translate it. It’s an enchanting novel set around an old farmhouse in northern Germany and its memories, some very dark, created by three generations of women.

A big thank you to Jamie for taking the time to answer my questions.

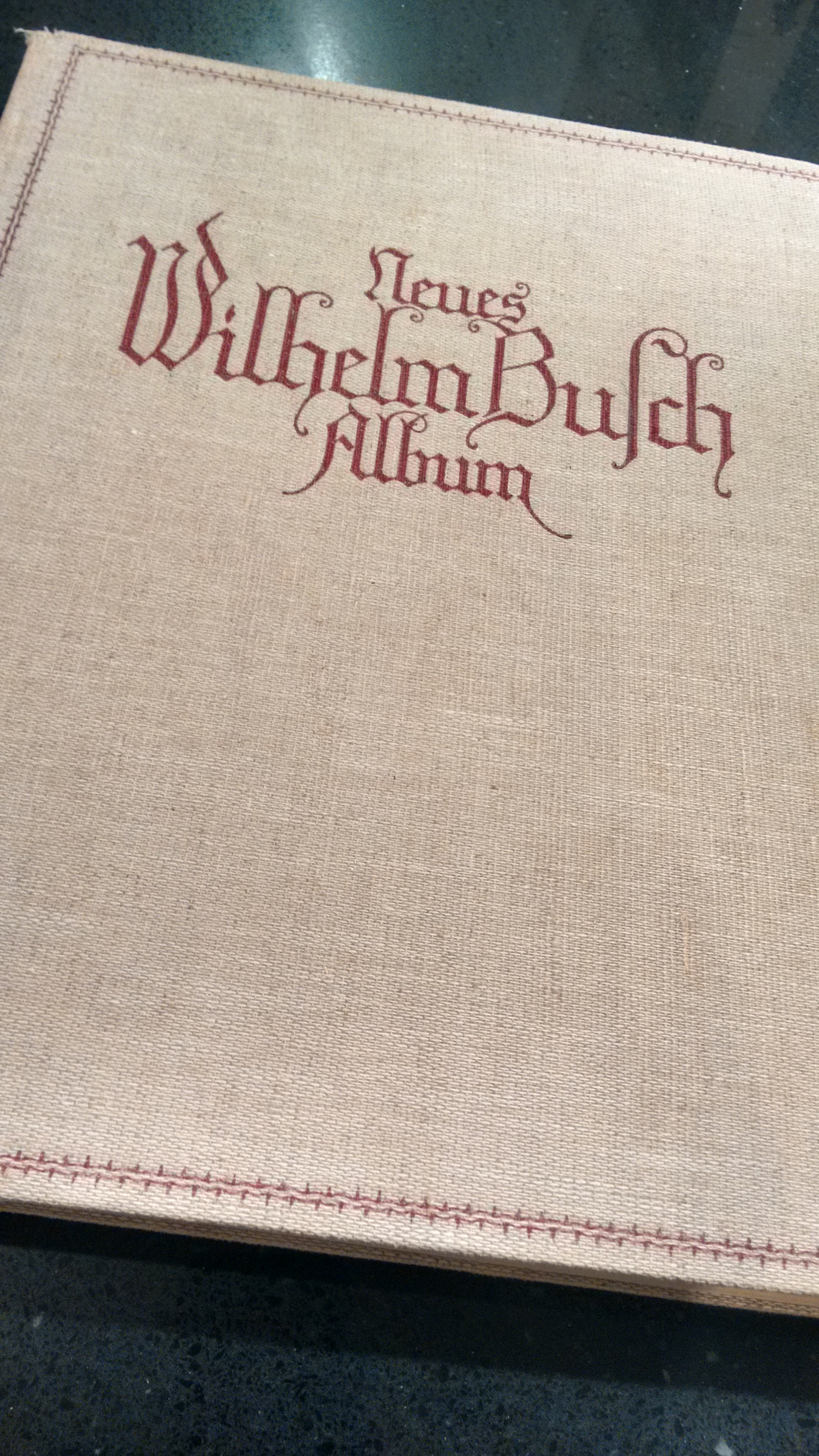

Other everyday farcical gems include the warring neighbours who beat the living daylights out of each other; the miller’s daughter who dispatches 3 thieves in grim fashion; the couple who trash their house while chasing a mouse; the guy driven to distraction by his toothache.

Other everyday farcical gems include the warring neighbours who beat the living daylights out of each other; the miller’s daughter who dispatches 3 thieves in grim fashion; the couple who trash their house while chasing a mouse; the guy driven to distraction by his toothache.