Wilhelm Busch (1832 – 1908) was a German humorist, poet and illustrator. His wood engraving illustrations satirised almost all parts of society but particularly Catholicism, religion in general, morality and everyday life in towns and villages across Germany. This beautiful anthology belonging to my mother, was given to her by a neighbour when she was 12. It was a firm feature of my own childhood. I vividly remember my sister and I leafing through the fine pages fascinated and vaguely disturbed in equal measure, because like Grimm’s fairy stories, some of Busch’s cautionary tales end badly for his characters.

Busch is best remembered for Max and Moritz the cheeky twosome who terrorise hardworking folk in their local community. This collection opens with the Max and Moritz series “Eine Bubengescichte in sieben Streichen” my translation “A rogue’s story in seven pranks” This is Dennis the Menace in double. Each “Streich” shows the boys carrying out pranks ranging from stealing cooked chickens, loading their teacher’s pipe with gunpowder or stuffing beetles under an elderly gent’s bedclothes.

All pretty fun and seemingly harmless until the last prank. After slicing rips into a farmer’s corn sacks, the farmer catches them and stuffs them into a bag.

The farmer takes them to the miller who promptly tips them into his mill, grinding them into small pieces.

The ground up bits of Max and Mortiz are gobbled up by the ducks. A really gruesome end.

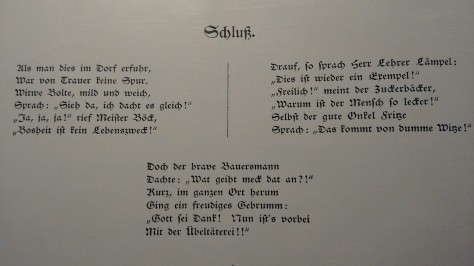

Busch ends the seventh prank with the villagers rejoicing at the demise of the young irritants!

Other everyday farcical gems include the warring neighbours who beat the living daylights out of each other; the miller’s daughter who dispatches 3 thieves in grim fashion; the couple who trash their house while chasing a mouse; the guy driven to distraction by his toothache.

Other everyday farcical gems include the warring neighbours who beat the living daylights out of each other; the miller’s daughter who dispatches 3 thieves in grim fashion; the couple who trash their house while chasing a mouse; the guy driven to distraction by his toothache.

The series called The holy Antony of Padua told over 10 chapters guides us through this priest’s life from birth to arrival at the pearly gates all the while mocking the church and its hypocritical practises.

Most of the illustrated stories are accompanied with verse, which honestly I sometimes found tricky to make out. This is due to the typeface which is a form of old German handwriting style called Suetterlin – really tricky to work out sometimes; even more difficult in Busch’s original hand (see below). This is featured later in the book which covers his life, career and includes prints of his sketches in progress. There is also some of his longer stories at the back of the album.

His illustrations are delightful if slightly grotesque. The characters are either portly with rosy cheeks and bulbous noses or they are skinny and wiry and frankly not to be trusted. The violence is slapstick. There’s always someone being bashed with a broom, falling through the floor or tripping and injuring themselves in some foolish act. All really good fun.

This is a beautiful anthology of a little known commentator of life in late 19th century Germany. I’ve enjoyed dipping into it again after years of having forgotten all about it.

Thanks to my mum for letting me borrow it!

I read this for German Literature Month

I don’t remember buying this book, but I was reminded I owned it when my good friend, the reader of True Blood (!) who I’ve mentioned before, pointed me in the direction of a BBC Radio 4 programme called Foreign Bodies. In this programme Mark Lawson presents a history of modern Europe through literary detectives and one of the episodes showcased Jakob Arjouni (still available as a

I don’t remember buying this book, but I was reminded I owned it when my good friend, the reader of True Blood (!) who I’ve mentioned before, pointed me in the direction of a BBC Radio 4 programme called Foreign Bodies. In this programme Mark Lawson presents a history of modern Europe through literary detectives and one of the episodes showcased Jakob Arjouni (still available as a