This time last year, I suggested we talk about love. Shall we do it again? I think we should.

This year has seen even less writing here than last year. Despite the lack of new “content” I got lots of visitors (that story’s for another time). Although I’ve not been active here, I’ve been writing bits elsewhere and short pieces for work. My year’s been hectic beyond belief with nothing more than everyday life and surviving it, which has inevitably impacted my reading choices. In the main, I’ve chosen slim volumes this year; brevity has been everything.

Writers have to work hard with short fiction (I’m not suggesting that writers of longer fiction don’t work hard btw). I continue to marvel at how writers use style and language to convey a story in a short volume. What they leave out tends to be almost as important as the words they include. Their omissions make the reader toil for their literary enjoyment. This is a good thing for a reader like me – I like to be challenged. I like filling in the gaps.

What I’m trying to say is that I’ve fallen in love with shorter fiction. I got so much enjoyment from all the slim volumes I’ve read this year – I’ve loved being immediately plunged into a plot, getting swiftly to the nub of the tale and being propelled to a conclusion. My head can’t seem to cope any more with layered plots and lengthy, multi-character tomes. I’ve felt a massive sense of achievement when putting books back on the shelf in quick succession. Also, from a practical perspective, small books are much easier to commute with!

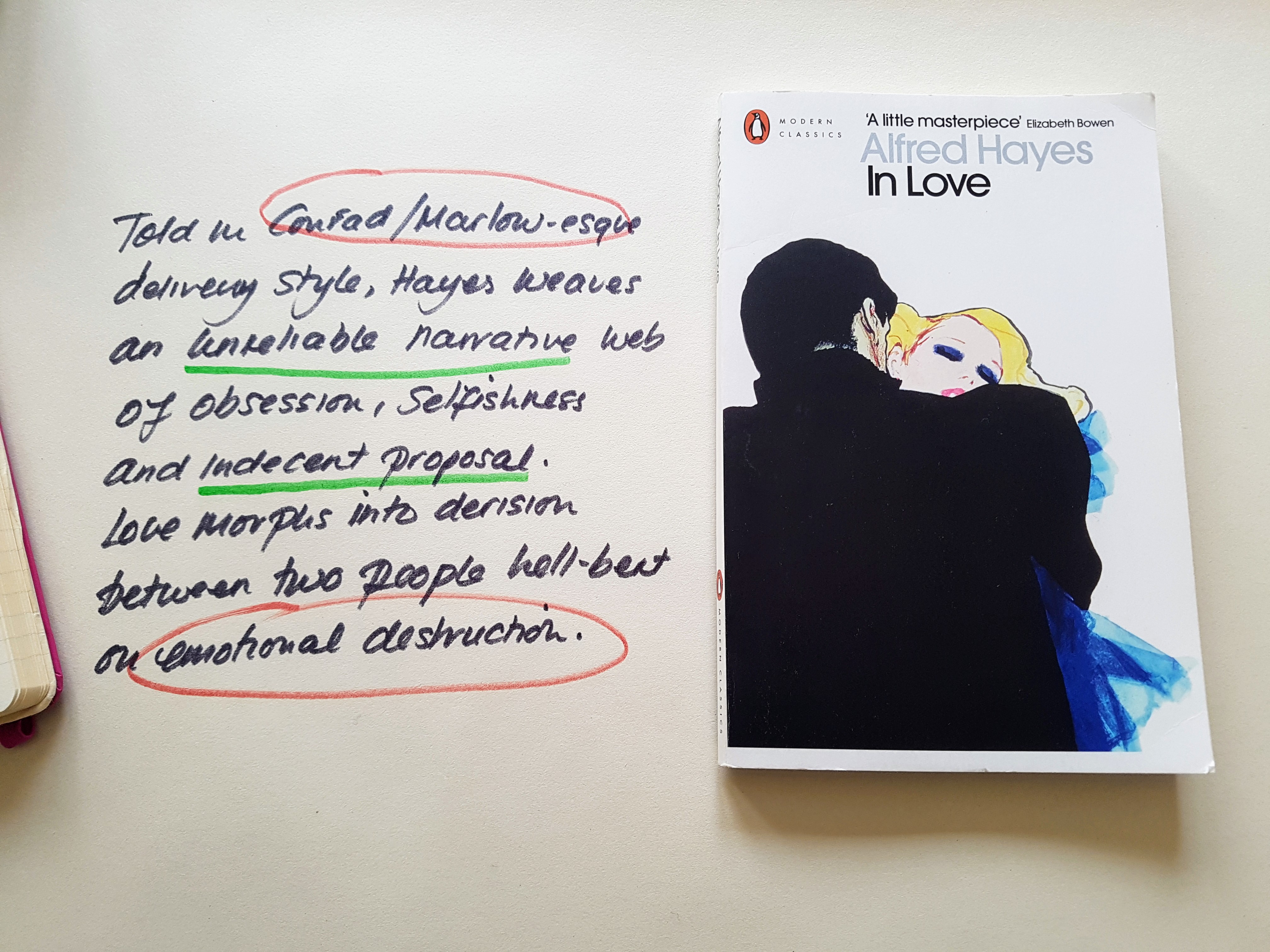

Much of what I’ve read this year has been about love – check the 3 books I wrote about earlier in the year as good examples. Other stand out titles include Ask The Dust by John Fante, Mothering Sunday by Graham Swift, In Love by Alfred Hayes, The Vegetarian by Han Kang, Hotel du Lac by Anita Brookner and The Tobacconist by Robert Seethaler. I could go on, but I’m already breaking all the rules of brevity in writing….

All these books deal with love in its myriad forms; passionate, obsessive, platonic, married, secretive, contented, fractious. You get the idea. Tin Man by Sarah Winman is a beautiful example of a love story about longing and grief. It affected me emotionally (not with Essex Serpent-ine tears, admittedly). I got a tight, heavy feeling in my chest that means I’ve read something moving. I felt enormous compassion and empathy for the main characters. The warmth I feel for it has encouraged me out of my hiatus.

Tin Man is a story of 3 people whose lives are linked through shared experience, compassion, friendship and love for each other. The story of their lives is revealed through Ellis and Michael’s recollections and memories, with Annie featuring as the glue that binds them and the reason for their estrangement despite being firm childhood friends. It’s tinged with regret and sadness overshadowed by a tragedy only hinted at until near the end and which prompts the memories. With her subtle and muted prose, Winman manages to evoke a feeling of loss and yearning for the relationship, creative and career decisions that might have been. How would their lives be, had they chosen differently? A feeling I suspect most of us can relate to.

The bond and connection between Michael and Ellis is emotionally strong. There is a touching moment when Michael worries about how he will be received by his old friend after a long period away with no contact. He turns up unannounced and is greeted as though he’s never been away – it made my heart sing.

For me, this book and that passage in particular perfectly articulates what love and friendship is about. When two people experience intimate emotional moments and connection they remain unbroken by time and space. The moments and connection eternally bind them, no matter how many days or years go by or how much geography separates them, the moments, even if fleeting, still exist in their memories as though they were recent encounters. (I’m getting a lump in my throat just writing those words, and I’ve not even had a festive sherry yet!).

Winman navigates us through the decades, deftly providing a glimpse of working life disappointments, trips of discovery to the South of France, life with Aids in the 1980s/90s and carefree summer days by the river. Over a few pages we become intimately involved with these characters until we understand them fully. I love writing that does this. I know I’ve told you very little about what TinMan is about; It’s about love – you don’t really need to know much more and in hindsight maybe that’s all I should have written.

In the spirit of this theme of love and friendship, I’m going to add the same line I closed last year’s post with, and it’s as fitting this year as it was then.

Care for others even when they don’t care for you. All. The. Time.

Last January I imposed vegetarianism on my family. Just for the month. We all survived. It was pretty good actually; the challenge of rethinking our entire menu choices appealed to my need to do something different to herald the new year. We are doing it again in 2018. The kids aren’t happy but took great delight in the realisation they can eat meaty things at the school canteen, which is beyond my jurisdiction.

Last January I imposed vegetarianism on my family. Just for the month. We all survived. It was pretty good actually; the challenge of rethinking our entire menu choices appealed to my need to do something different to herald the new year. We are doing it again in 2018. The kids aren’t happy but took great delight in the realisation they can eat meaty things at the school canteen, which is beyond my jurisdiction.